“Humans cannot live without illusions. For the men and women of today, an irrational faith in progress may be the only antidote to nihilism. Without the hope that the future will be better than the past, they could not go on.”

― John Gray

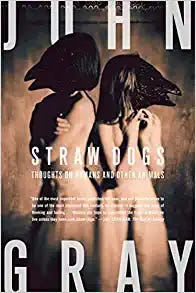

The book "Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals" by British philosopher John Gray is perhaps one of my favorite philosophical books written in the 21st century. But it’s not for the faint of heart.

It’s a profound yet challenging book — “challenging” not in the sense of comprehension but in a way that will surely poke at established beliefs and the unquestioning “ray of sunshine” worldview we’re all supposed to bathe in.

It’s a book that takes a hammer to our preconceived notions and the conventional wisdom that we rarely take the time to reexamine.

The prevailing theme of Gray’s provocative philosophy is that human beings are not as unique or special as we often think we are, and that our attempts to control the world around us are not only futile but ultimately the root of our many woes.

“Action,” in the words of Gray, “gives us consolation for our inexistence…a refuge from insignificance.”

Gray also challenges many of the revered assumptions of Western modernity, including the idea of progress and the belief in the power of science and technology to solve all of our problems. As he writes, "Science will never be used chiefly to pursue truth, or to improve human life. The uses of knowledge will always be as shifting and crooked as humans are themselves. Humans use what they know to meet their most urgent needs – even if the result is ruin."

Overall, Straw Dogs, in the words of writer Will Self, “is that rarest of things, a contemporary work of philosophy devoid of jargon, wholly accessible, and profoundly relevant to the rapidly evolving world we live in.”

The following is a brief FORWARD to the paperback version of the book written by the author himself, John Gray.

Straw Dogs is an attack on the unthinking beliefs of thinking people.

Today liberal humanism has the pervasive power that was once possessed by revealed religion. Humanists like to think they have a rational view of the world; but their core belief in progress is a superstition, further from the truth about the human animal than any of the world’s religions. Outside of science, progress is simply a myth.

In some readers of Straw Dogs this observation seems to have produced a moral panic. Surely, they ask, no one can question the central article of faith of liberal societies? Without it, will we not despair? Like trembling Victorians terrified of losing their faith, these humanists cling to the moth-eaten brocade of progressive hope.

Today religious believers are more free-thinking.

Humanists turn to Darwin to support their shaky modern faith in progress; but there is no progress in the world he revealed. A truly naturalistic view of the world leaves no room for secular hope.

Humanism is not science, but religion – the post-Christian faith that humans can make a world better than any in which they have so far lived.

The idea of progress is a secular version of the Christian belief in providence.

Belief in progress has another source. In science, the growth of knowledge is cumulative. But human life as a whole is not a cumulative activity; what is gained in one generation may be lost in the next.

In science, knowledge is an unmixed good; in ethics and politics it is bad as well as good. Science increases human power – and magnifies the flaws in human nature. It enables us to live longer and have higher living standards than in the past. At the same time it allows us to wreak destruction – on each other and the Earth – on a larger scale than ever before.

If the hope of progress is an illusion, how – it will be asked – are we to live? The question assumes that humans can live well only if they believe they have the power to remake the world.

Yet most humans who have ever lived have not believed this – and a great many have had happy lives. The question assumes the aim of life is action; but this is a modern heresy.

For Plato contemplation was the highest form of human activity. A similar view existed in ancient India. The aim of life was not to change the world. It was to see it rightly.

Today this is a subversive truth, for it entails the vanity of politics. Good politics is shabby and makeshift, but at the start of the twenty-first century the world is strewn with the grandiose ruins of failed utopias. With the Left moribund, the Right has become the home of the utopian imagination. Global communism has been followed by global capitalism. The two visions of the future have much in common. Both are hideous and fortunately chimerical.

Political action has come to be a surrogate for salvation; but no political project can deliver humanity from its natural condition. However radical, political programmes are expedients – modest devices for coping with recurring evils.

Hegel writes somewhere that humanity will be content only when it lives in a world of its own making.

In contrast, Straw Dogs argues for a shift from human solipsism. Humans cannot save the world, but this is no reason for despair. It does not need saving. Happily, humans will never live in a world of their own making.

If anyone is interested in a little more in depth understanding of Mr. Gray's philosophy, here's a brief 10 minute interview well worth your time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=ft10Kx4Enos&fbclid=IwAR3ulAFLYVG_01nwmHTskKKrilMj-R-9iFr7Lh9zNzpX51DcGA8w1uY6JX0

I think I'll get this for my friend. It'll piss him off but in an appreciative way. In any case, I agree about progress being a myth and that thinking people have "unthinking ideas." An assault upon that cluster of annoying ideas has been a long time coming.

That being said, while I have to read it first it doesn't sound like Gray gives us anything new. The book sounds like it tries to spank us in the ass with an acceptance of anti-humanism, which isn't a healthy mentality to live with irrespective of how much we value progress. Can't progress be simply critiqued in and of itself? It appears Anthropocene, and the idea that we are animals and not exalted humans comes from science and evolution, meaning it comes from the same flawed source as the humanists and believers in scientism relying on Darwin. And no matter what a philosopher chooses to argue, look at our cities and our creations: then point to an animal that has come close to doing the same thing. We are different from other animals: that's a fact we only need eyes to determine. (I don't accept that whole postmodernist shtick where it's all an illusion: and if it is, only God could create that, which gives Christianity the victory anyway. Which is fine with me, but even then it wouldn't make sense for God to make it all an illusion because if I'm engaging in the sin of gluttony, then isn't my sin just an illusion too?)

Correct me if I'm wrong. But good recommendation. I'll be sure to check this book out.