Bukowski: The Crowd is the Gathering Place of the Weakest; True Creation is a Solitary Act

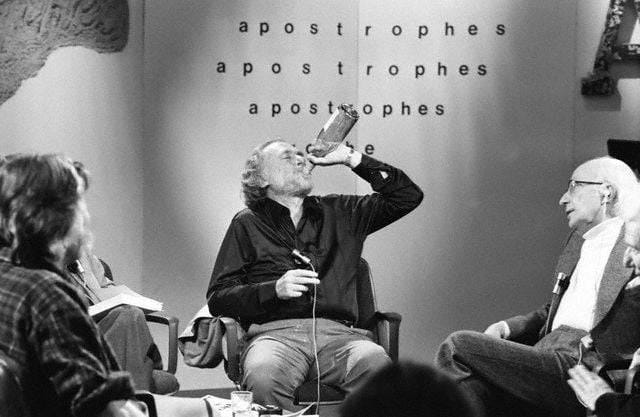

Bukowski's Interviews

To me it is still one man alone in a room creating Art or failing to create Art. All else is bullshit.

— Charles Bukowski

Charles Bukowski is the kind of artist you either despise with every fiber of your being or crown as the underground’s grizzled monarch.

His poetry is a cocktail of vulgarity, grime, sharp wit, criticism, elitism, and a hefty dose of self-loathing. On the other hand, Bukowski wrote with stunning beauty about creativity and the messy yet marvelous landscape of the human soul. You might catch this in his gem of a poem, Bluebird, where he pulls back the curtain to reveal both the mud and the meadows of his own heart.

He once said in an interview: “Well, if there is a darkness in my writing it is a darkness that is trying to work into the light or if I can’t make it into the light it is a darkness that lives somehow and anyhow within and against all odds. Just for the hell of it.”

Bukowski was a fearless writer, never one to shy away from shining a spotlight on humanity's murkier corners. He lived life on his own terms, mostly poverty-stricken and forlorn, so that he could pour everything into his art. He wrote almost every day, hangovers and all, and chose the chaotic ride of a creative life over the mind-numbing safety of a cushy, predictable existence.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti once said:

“If you're going to be a writer you should sit down and write in the morning, and keep it up all day, every day. Charles Bukowski, no matter how drunk he got the night before or no matter how hungover he was, the next morning he was at his typewriter. Every morning. Holidays, too. He'd have a bottle of whiskey with him to wake up with, and that's what he believed. That's the way you became a writer: by writing. When you weren't writing, you weren't a writer.”

Butkowski, too, was an exquisite conversationalist. Watching a few of his interviews recently, I couldn’t help but think how some of his answers to the questions posed could be poems in themselves. He never said the obvious thing, never cliche, and always amusing.

In his many interviews throughout the years, Bukowski delivered his lines with razor-sharp precision, wit, and humor. He was at ease in front of an audience and never short on charisma. It’s been said that he fine-tuned those verbal skills as a young "Barfly," entertaining bartenders and boozehounds alike in dives across the nation.

Think of him as a barstool comedian with a poetic twist—part philosopher, part stand-up act, always ready with a punchline or a punch to the gut.

I want to share this with you today — the wit and wisdom of his interviews.

You can find this commentary in Charles Bukowski: Sunlight Here I Am: Interviews and Encounters 1963-1993, published by Sun Dog Press, 2003. It’s a marvelous book to own and read in its entirety.

“Most of us are born poets. It is only when our elders get to us and begin to teach us what they teach us that the poet dies.”

— Charles Bukowski

Question: How come you’re so ugly?

Bukowski: I presume you’re talking more about my face than about my writing. Well, the face is the product of 2 things: what you were born with and what has happened to you since you were born.

My life has hardly been pretty — the hospitals, the jails, the jobs, the women, the drinking. Some of my critics claim that I have deliberately inflicted myself with pain. I wish that some of my critics had been along with me for the journey. It’s true that I haven't always chosen easy situations, but that's a hell of a long way from saying that I leaped into the oven and locked the door.

Hangover, the electric needle, bad booze, bad women, madness in small rooms, starvation in the land of plenty, god knows how I got so ugly. I guess it just comes from being slugged and slugged again and again, and not going down, still trying to think, to feel, still trying to put the butterfly back together again…it’s written a map on my face that nobody would ever want to hang on their wall.

Sometimes I’ll see myself somewhere…suddenly…say in a large mirror in a supermarket…eyes like little mean bugs…face scarred, twisted, yes, I look insane, demented, what a mess…spilled vomit of skin…yet, when I see the “handsome” men I think, my god my god, I’m glad I’m not them.

Question: Do you think poetry will be valid in a hundred years from now?

Bukowski: No, and it’s not valid now. I’d rather drink buttermilk. Poetry has disgusted me more than any other art-form. It’s held all too damn high and mighty holy. It’s a pasture for fakes. Even when the boys try to talk straight they talk over-straight, rather borrowing a stance which is as bad as the roses and moonlight stance, the obtuse stance, the clever stance, the concrete stance, all the stances…

To expect power out of garbage is to expect too much in one hundred years. In fact, poetry has gone back.

Question: What do you feel the purpose of a poet should be during a time of revolution?

Bukowski: Drink and fuck, eat and shit, sleep, stay clothed, stay alive, stay away from guns and mass-ideals and mass-history and find whatever single truth might be found in a single man so that when the so-called mass-truths and ideals and ideas decay again that he (the poet) and they (the tricked) can have more to hold to than rubble and rot and tombstones and treachery and the waste of hysteria and Time.

Question: How come you’re a poet anyway?

Bukowski: How come you ask so many stupid questions?

Question: Some still think your poems are a waste of time.

Bukowski: What isn’t a waste of time? Some collect stamps or murder their grandmothers. We are all just waiting, doing little things and waiting to die.

Question: John Lennon once said, “Art is life. The trouble with most up-and-coming artists is they’re too busy with art to have time to live.” Comment?

Bukowski: From what I know, John Lennon never produced anything real or worthwhile nor was the way he lived worth a twit either.

Question: Gore Vidal once said that, with only one or two exceptions, all American writers were drunkards. Was he right?

Bukowski: Several people have said that. James Dickey said that the two things that go along with poetry are alcoholism and suicide. I know a lot of writers, and as far as I know they all drink but one. Most of them with any bit of talent are drunkards, now that I think about it. It’s true.

Drinking is an emotional thing. It joggles you out of the standardism of everyday life, out of everything being the same. It yanks you out of your body and your mind and throws you against the wall. I have the feeling that drinking is a form of suicide where you're allowed to return to life and begin all over the next day. It's like killing yourself, and then you're reborn. I guess I've lived about ten or fifteen thousand lives now.

Question: The Kennedy assassination and its attendant phenomena are big news once again. Do you favor any of the current conspiracy theories? Are you even interested?

Bukowski: I think you guessed it. I am just about not interested. History, of course, makes a president big news and the assassination of one more so.

However, I see men assassinated around me every day. I walk through rooms of the dead, streets of the dead, cities of the dead; men without eyes, men without voices; men with manufactured feelings and standard reactions; men with newspaper brains, television souls and high school ideas.

Kennedy himself was 9/10ths the way around the clock or he wouldn't have accepted such an enervating and enfeebling job -- meaning President of the United States of America. How can I be concerned with the murder of one man when almost all men, plus females, are taken from cribs as babies and almost immediately thrown into the masher?

Question: Do you hate people in general?

Bukowski: No. Quite the contrary. But as I said, I hate crowds. Crowds are shit, and the greater the crowd, the more the shit stinks. Take twelve men in a bar, drinking and kidding. They disgust me, they’ve got no identity, no life.

But take each one of those men alone, listen to what he’s got to say, see what’s bothering him—and you’ve got a unique human being. That’s what my writing is all about.

And also that there’s got to be something else.

I’m a dreamer, I’d like a better world. But I don’t know how to make it better. Politics is not the way. Government is not the way. I don’t know the way. I’m just discouraged that men and women have to live their lives the way they do. It’s painful to them, and it’s painful to me, but I don’t know the way out. So all I can do is write about the pain of it.

Question: Your poem “friendly advice to a lot of young men” says that one is better off living in a barrel than he is writing poetry. Would you give the same advice today?

Bukowski: I guess what I meant is that you are better off doing nothing than doing something badly. But the problem is that bad writers tend to have the self-confidence, while the good ones tend to have self-doubt.

So the bad writers tend to go on and on writing crap and giving as many readings as possible to sparse audiences.

These sparse audiences consist mostly of other bad writers waiting their turn to go on, to get up there and let it out in the next hour, the next week, the next month, the next sometime.

The feeling at these readings is murderous, airless, anti-life. When failures gather together in an attempt at self-congratulation, it only leads to a deeper and more, abiding failure. The crowd is the gathering place of the weakest; true creation is a solitary act.

Question: What do you think a young poet starting out today needs to learn the most?

Bukowski: He should realize that if he writes something and it bores him it’s going to bore many other people also. There is nothing wrong with a poetry that is entertaining and easy to understand. Genius could be the ability to say a profound thing in a simple way. He should stay the hell out of writing classes and find out what’s happening around the corner. And bad luck for the young poet would be a rich father, an early marriage, an early success or the ability to anything very well.

You can complement this post with — Bukowski on Writing and the Horror of Wasted Lives and Jim Harrison’s brief essay on Bukowski — The Pleasures of the Damned.

You can also check out the Poetic Oulaws shop. It's nothing big, but we have coffee mugs and T-shirts for sale. Thank you for supporting this page!

I haven't been subscribed to this substack for long, but content like this is why I initially subscribed. I have you to thank for introducing me to Bukowski. I read year round and have for decades, but somehow I had never heard of him. In the last three months or so I've read: "Post Office," "Women," "Hollywood," and "Factotum" (in that order). I'm also working my way through one of his poetry collections. We're told we should be reading the "Classics," and I do, but nothing has ever grabbed me like Charles Bukowski. He writes about real lived human experience like no one else. Anyway, thanks again, and keep it coming!

This article explores the complexity and uniqueness of Charles Bukowski's art, which Erik memorably describes as "a cocktail of vulgarity, grime, sharp wit, criticism, elitism, and a hefty dose of self-loathing." But it is also (and this is the point) an art that captures "the messy yet marvelous landscape of the human soul." What a fine, balanced article this is!