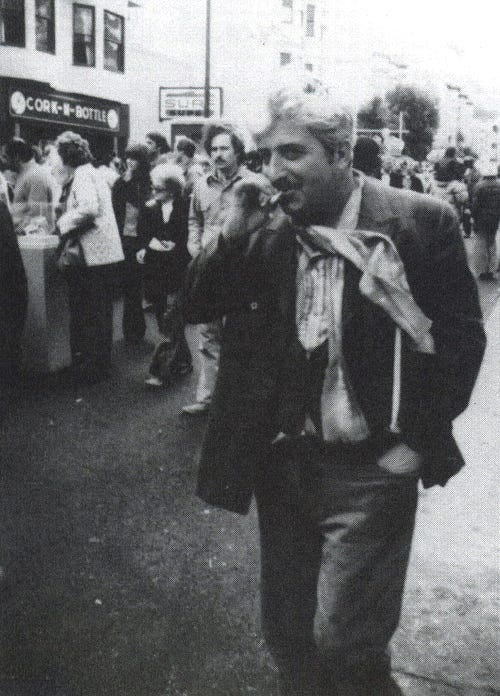

“Imagine Jack Micheline, half pint riding the left hip pocket of his holy corduroys, walking sunset, one arm around the sky, the other around the Earth, as he rages against The Clowns who’ve denied The Poet’s Blood…”

-- Wanda Coleman

He was born in the Bronx on the brink of the Great Depression. Barbed wire and asphalt, soup lines and madness in the cold wretched winter of discontent. A nation on the verge. He grew up there. America, 1930’s. Early in life, Jack took to the road, a wandering young man with no resources, roaming and roaring across the land like a wild nomad. He never did drink himself to death like Kerouac or die mysteriously like Cassady on some lonesome railroad track in Mexico but goddamnit he did fall into a ditch in Cicero, Illinois and rise like a frayed phoenix a born-again poet. Harvey Martin Silver was his birth name but he changed it to Jack, taken of course from the famous American tramp-writer, Jack London, a man unrivaled in the art of living dangerously. Micheline’s first poem was penned after watching two bums brawl over a bottle of wine in the cold streets of the city. From then on, he wrote about the poverty-stricken workers and artists, petty criminals, whores and addicts. Unadulterated life in the streets. This was 1954, the time of Beats, the time of post-war conformity and middle-class sensibilities and that fierce, rebellious hunger for LIFE seething in the hearts of the youth. For a little money Micheline took up odd jobs— clerk, actor, beggar, dishwasher, union organizer. Deliberately detached from the social ladder, free from the chains of societal norms and the nine-to-five stability, Jack was a solitary figure making his way through the new America writing his poems and painting, surrendering comfort and security for art and escapades. He somehow got in with the down-and-out Beat poets before the Beats became commercialized and he read his poems on city corners and in cafés and pool halls. He won a poetry contest and finally got published in a magazine along with the works of Philip Whalen, Diane di Prima, and Allen Ginsberg. Against all odds, Micheline had something. He got his first book of poems published and was fortunate enough to have the great Jack Kerouac write the forward. Micheline spent the better part of the 1960’s writing poems and traveling around Europe finally settling down at the end of that rip-roaring decade on the West Coast where he became friends with the beer-swigging Los Angeles poet Charles Bukowski. Bukowski, rarely bent on showing admiration for other writers and poets, had this to say about ole’ Jack: “Micheline is all right—he’s one-third bull shit, but he’s got a special divinity and a special strength. He’s got perhaps a little too much of a POET sign pasted to his forehead, but more often than not he says the good things–in speech and poem–power- flame, laughing things. I like the way his poems roll and flow. His poems are total feelings beating their heads on barroom floors. I can’t think of anyone who has more and who has been neglected more. Jack is the last of the holy preachers sailing down Broadway singing the song. Going over all the people I’ve ever known, he comes closer to the utmost divinity, the soothsayer, the gambler, the burning of stinking buckskin than any man I’ve ever known.” Jack once told a story about how Janis Joplin asked him to write her a song. He wrote it, “great song too,” he proclaimed with a shit-eatin' grin. But he said that her mind was far too gone by then. So it never got sung. No one really believed him. Micheline, a dying breed indeed, was an outlaw in life and with the written word who was shunned by the literary world. He was ignored by all the major publishing houses along with the tweed jackets of academia. Hell, he mostly held company with the vagabonds and bohemians and the street people anyway. He never did conform or try to appease. His poems were like a crumpled page ripped from his ragged soul that reflected the life in the cold streets of America. He wanted to give voice to the disenfranchised – "The literary revolution was a put up job. A middle-class revolution, a paper tiger, a media hype at best. It's time for poor voices not heard from, hidden in the dark corners of America. Voices crushed on skid row, walking the streets & highway out of their minds." He was “a true minstrel, living in our own sad, desperate times,” wrote Diane diPrima. I can still hear Micheline howling into the demented wind: "I am fifty-two, live alone, considered some mad freak genius In reality I am a fucked up poet who will never come to terms with the world No matter how beautiful the flowers grow No matter how children smile No matter how blue is the bluest sky… Tomorrow is never better..." February 27th, 1998, I was an 18-year-old senior in high-school somewhere in Florida, green to life, about to join the Navy. Jack was on a commuter train somewhere outside of San Fran where he died suddenly of a heart attack, probably scribbling a poem in his tattered notepad like he always did on buses and trains. He was discovered by the transit police on that late Friday morning. He was 68 years old. Sing it Jack, sing us one last one: Everywhere I go is beauty, trees illuminated street lights glowing in the darkness I want to run up to strangers and kiss them but there is too much noise men kill each other I’m sick and tired of seeing sad faces stop that bastard machine everyone is God and Holy a spike is ripping at my throat I smell a fragrance of a rose everywhere I go is beauty.

Thanks so much for reading. You can find me around the internet at the following: Medium: https://medium.com/@erikrittenberry Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/erik.rittenberry Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/erik_rittenberry/

I saw Jack perform his poem 'Cockymoon' in person in San Francisco. I vividly recall his body language, bent over and to the side, swirling the air with his finger, and his jack-o-lantern grin.

I knew Jack casually towards the last couple years of his life. I tried to broker a deal with his manuscripts and UC Berkeley Bancroft Library. Did not work out.